What is Reverb in Music and How to Use It Like a Pro

- Recording

- 03.11.2024

- 10 min

In a purely definitional sense, reverb (short for reverberation) is the extension of a sound beyond its natural endpoint. This process can be natural, using the size and dynamics of a recording space, or synthetic, using digital audio effects. For example, when a guitar string is plucked the string will stop vibrating at a certain point, but the sound waves emitted by the guitar will continue to spread through the room, bouncing and reflecting off of surfaces before eventually fading to nothing. Where this process is authentic in acoustic recordings, synthetic reverb only gives the illusion of reverberation.

If you are attempting a natural, acoustic technique, the length and dynamics of the reverb will depend on a variety of factors. If you want very little reverb, you might choose to record in a small room with sound-absorbent walls or curtains. Alternatively, if you wanted lots of reverb, you could record your instrument in a church, where the walls are not only tall but also highly reflective. Furthermore, you can adjust the levels and dynamics of the reverb by changing the position of your microphone(s) or adjusting the environment of the recording. Unfortunately, this makes the process of adjusting acoustic reverb difficult. Luckily, with the exception of classical composers and gospel artists, acoustic reverb is rarely used in contemporary popular music. With modern recording practices and the rise of at-home DIY production, it is much more common for artists and producers to use the easier and more flexible route: digital reverb.

While acoustic reverb is generally difficult to manipulate and tweak, digital reverb allows producers to make more subtle, controlled adjustments to their reverb settings. Digital reverb can be achieved through the use of pedals, inbuilt instrumental effects, and most importantly, Virtual Studio Technology (VST) plug-ins. The most common of these, and the focus of this article is the VST reverb effect plug-ins. In short, these are software interfaces that simulate recording studio hardware in order to make these effects more accessible to regular producers. In addition to creating a synthetic reverberation, many plug-ins will have a variety of presets which imitate real recording environments.

For example, a team of audio engineers will have saved a specific configuration of the settings of the plug-in in order to imitate the reverberation of a hall or theater. This saves a lot of work for the producer while also allowing them to make any further tweaks to the sound. Using digital reverb also allows the artist to choose from a huge selection of plug-ins made by a variety of audio engineering companies. This brings both flexibility and diversity of sound to the user. Though many digital reverb plug-ins will contain different and wide-ranging settings, there are generally a number of consistent settings dials on every reverb plug-in. These are worth knowing and understanding.

Room reverb is the most simple of the options and is simply a plug-in (or mode) imitating the sound of a standard room. This is most commonly used for genres that require little embellishment like folk or jazz.

This type of reverb has a short decay (reverb tail) and works well on drums, vocals, acoustic and synth instruments.

This is a replication of the reverberation from a large concert hall. These are halls designed for the enjoyment of music and are ideal for anything from attempts at imitating live music to pop balladry to orchestral recordings.

Hall reverb has long reverb tail and sound good on vocals, pads, effects, etc.

Prior to the invention of digital reverbs, studio engineers, who were unable to afford concert halls, would create reverb by recording artists in medium-sized rooms with highly reflective surfaces. These rooms were called chambers and had unique dynamics and character.

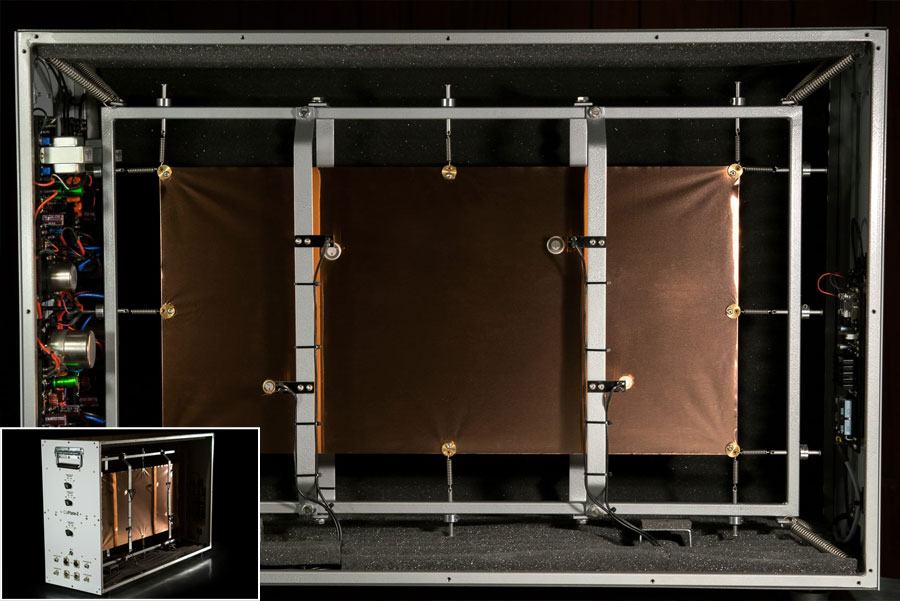

Plate reverbs, used on many Beatles and Pink Floyd records, utilize electromechanical transducers to create vibrations through large sheets of metal. Those vibrations are then recorded as audio by contact microphones. They are known for their uniquely clean sound and smooth tail. Often, plug-ins will replicate this reverb technique.

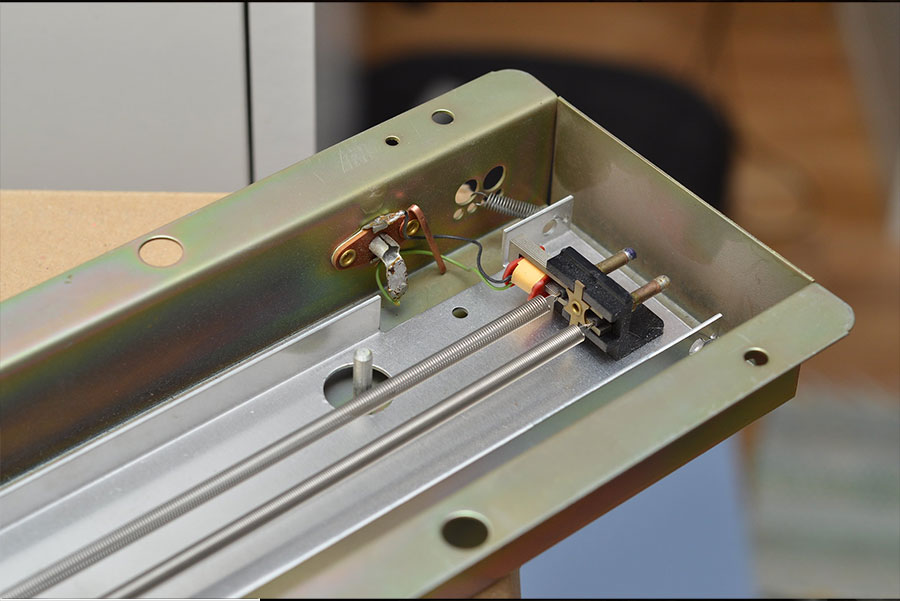

Spring reverbs function similarly to plate reverbs. Rather than a large metallic plate, spring reverbs use a small metal spring with a transducer at one end and a pick-up at the other. Due to their small size, they were often used for guitar amplifiers. Plug-ins will replicate the sound of this mechanism.

Early reflections are the first one or two clearly defined reflections off of the surfaces of the recording space. These are the vital reflections that communicate the size and dynamics of the room to the listener. Late reflections occur when the sound has reflected off of the surfaces multiple times and has formed an amorphous “reverberation”.

The dry sound is simply the unaltered sound of the instrument. The wet sound is the separated reverberation. Thus, if there is a dial for wet and dry values, you will be adjusting the volume of each part. These simple values can be put to use in surprisingly interesting ways.

Pre-delay is the period of time between the dry signal and the reverb signal. Normally, this is set very low to create a natural-sounding reverberation. However, occasionally a producer might create a large pre-delay in order to create a unique or experimental sound.

In traditional music production terms, decay is the period of time that a sound takes to go from its peak to its resting level while the note or effect is still being used. However, though this is the technical description, often when decay is used in relation to reverb it simply means the time before the sound fades away to nothing. Thus, the higher the decay, the longer the reverb takes to fade.

You may find this setting in some reverb plugins that have reverb envelope.

Attack is the period of time that an audio signal or note takes to go from nothing to its maximum value or peak. This is a graduated process, meaning it builds up to its maximum amplitude. When applied to reverb, this means the amount of time before the reverberating sound reaches its peak. If this is set very high, it can create a graduated gap between the original dry sound and the wet sound (the reverb). Note that this is different to a pre-delay as with attack the sound grows over a variable time.

A preset is a group of settings of the reverb plug-in designed for specific instrument or which replicate the reverberation of a specific environment. The names of these presets are usually self-explanatory – drums room, church, concert hall, theater, bathroom, garage, etc.

Reflectivity refers to the reflectivity of the synthetic walls which the plug-in has simulated. The higher the reflectivity, the more the plug-in will synthesize the sonic environment of a highly reflective recording space (i.e. a cathedral). This might extend the length of the reverb or increase its intensity. One might utilize this if they are seeking to achieve a grandiose or spacey sound.

This refers to the size of the synthesized room that the plug-in is replicating. If a producer increases the size, the plug-in will replicate a larger room such as a church or cathedral.

EQ or Equalization is the process of adjusting the balance of frequencies within an audio signal. For example, if a producer wants to make a low-end track, they might lower the high frequency signals and increase the low-frequency signals. Often, producers will use equalizer (or EQ) to negate any irritating or abrasive tones from their sound.

When applied to reverb, EQ simply applies this process to the sound of the reverb. This can also take the form of low and high cut dials. As opposed to the more controlled and detailed EQ chart, these dials allow you to cut out signals below or above a certain frequency. For example, if the low cut dial is at 120Hz, the plug-in will filter out signals below this frequency. The high cut dial will filter out signals above the specified frequency.

1. Don’t overuse reverb. Often when amateur producers begin to use reverb, there is a tendency to add it to most elements of the track with little restraint. This is partly because reverb makes most things sound grandiose and more dramatic. In reality, however, when too much reverb is used, it can make a track sound too spacey and even artificially grand. For example, though a thick reverb on a snare can sound great, reverb on an entire drum pattern might sound too muddy.

2. Do use reverb to cover up any minor blemishes. Though this should be used sparingly, if your guitar finger-picking technique is not perfect, often a tiny amount of reverb can help paper over the cracks. It will help to disguise any minor errors. However, do not use this for everything, and make sure your focus is on perfecting your craft before adding effects.

3. Don’t use too much reverb on the vocals. Often singers will apply huge amounts of reverb to their voice. Of course, this can be beneficial at times, but often the singer ends up being drowned in the reverb. This can make the vocals less engaging and sometimes even bland. As with all effects, moderation is advised.

4. Do use reverb to make tracks lush. Often the dry sounds of instrumentation can be grating and sterile. A vocal with no reverb will often sound lifeless. Even the tiniest amount of reverb can help make a sound more effective.

5. Don’t use an overly long decay on reverb. Often when reverb extends for too long, the sound becomes muddy and cluttered. If you are working within popular genres such as rock, pop, or hip-hop, it’s usually best to be conscious of abusing your reverb plug-in. Within ambient pieces of music or soundtrack work, the producer usually has more freedom to use long-lasting reverbs.

6. Do experiment. Reverb is a hugely effective and versatile tool. Though one could simply attempt to replicate the sound of an acoustic reverb, a producer can also break the traditional rules of reverb. For example, an experimental producer might want to put a large pre-delay on the reverb in order to create a strange experience for the listener. This would place a counterintuitive gap between the dry sound and the reverberation. Alternatively, an ambient composer might turn the dry sound to zero. This would allow a musician to create a swell in instrumentation that is otherwise impossible. Some guitarists will do this when creating more ambient pieces. In short, play around with the multitude of settings available to you. This might allow a producer to create an original sound or tone.